I was able to avoid the rain that had been forecast until this morning when a light shower started as I headed East toward the Sheraton and the last day of the ACS conference this year. I was very excited to attend the first morning session called “Self-Starter: Developing and Harnassing Your Own Microbes” at 9:00am. Unfortunately this is one of those timeblocks when I want to go to several of the sessions, and I had to pick one. Dave Potter of Dairy Connection is leading “Expand Your Brand With Yogurt” which ought to have a lot of good information on the different mixes of starter culture available (especially since they discontinued my favorite mix a year ago!), as well as different ways people are marketing their yogurt — you can always pick up some good tips at ACS sessions. And then there is another session, moderated by Rachel Perez who moderated the Unconventional Pairing session yesterday, called “The Evolution of Artisan Cheese in America.” The panel includes Allison Hooper of Vermont Creamery, Mary Keehn of Cypress Grove, and Judith Schad of Capriole…all ladies, and all Goat Laidies! That says a lot about the modern evolution of artisan cheese making in both the US (VT, CA, and IN respectively represented on the panel) as well as in Maine. I hope we get to hear about these sessions from some of the others in the Maine Gang later on.

LET’S GET IT STARTED!

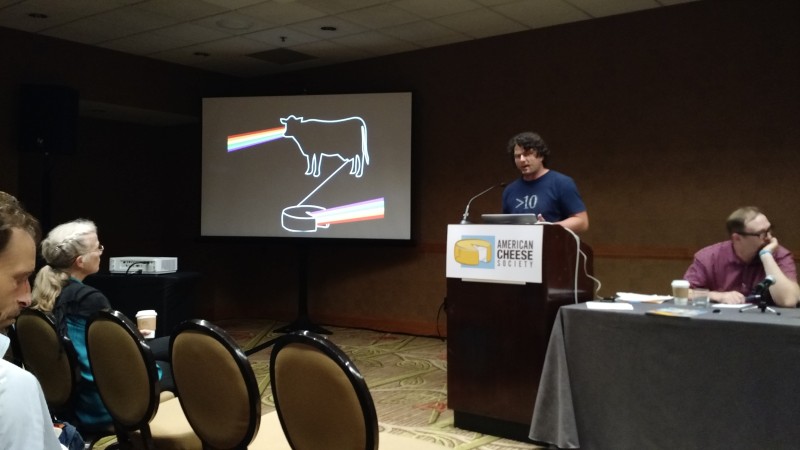

Most of us have taken at least one class with Peter Dixon, and for those of us who arrended the Culture Workshop he taught for us in November 2016 at Pineland Farms you will be familiar with Peter’s presentation. However Dixon was preceeded by Mateo Kehler, founder (with his brother) of Jasper Hill Farm (and then The Cellers at Jasper Hill) in northern Vermont. Kehler described the deep deep dive they have done into the native micro-biology of their dairy farm and aging facility in attempt to really understand, at a scientific level, what makes their cheeses unique. What he discovered along the way was that they weren’t acually farming dairy cows and turning that milk into cheese; instead Jasper Hill Farm is really “farming microbes.”

Sister Noella, Rachel Dutton, and Ben Wolfe answer questions after their presentation at ACS Montreal 2011

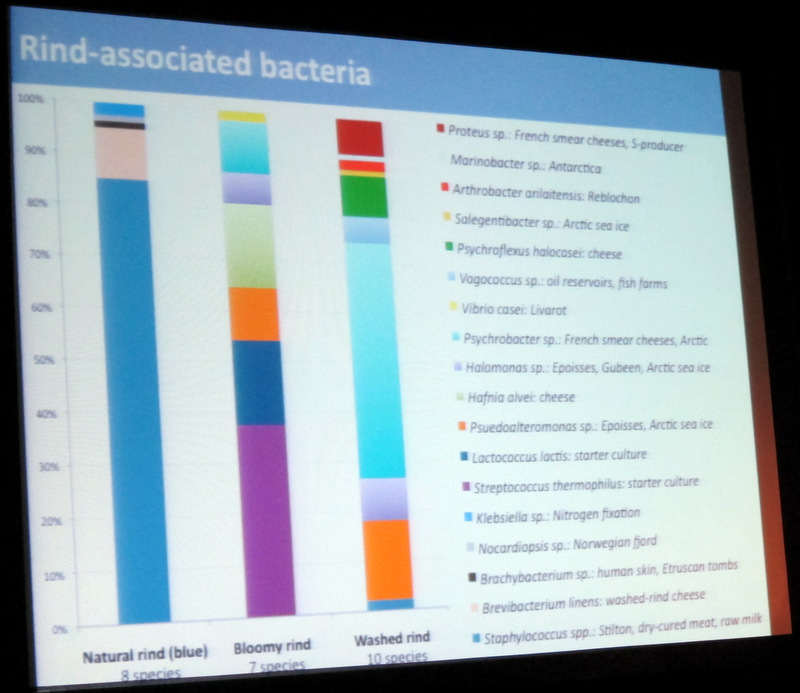

WAY way back at the Montreal ACS Conference in 2012 I (along with Caitlin and Brad Hunter) attended a session featuring Sister Noella talking about her own scientific dive into cheesemaking. About midway throught the session she introduced a fresh faced young woman who turned out to be Dr. Rachel Dutton who was then working on a fellowship at Harvard studying microbial communities. She had started her research studing the microbiology of ocean oil slicks, but she found them difficult to model and study, so she turned to another well known but little studied microbial community: cheese rinds. Together with her (then) post-doc partner, Dr. Ben Wolfe, who studied funguses (like Geo. c.) they presented some of their initial findings of the inner workings of the microbial and fungal communities they found in the cheese cellers they had partnered with: Jasper Hill Farm.

Fast-forward to the 2014 ACS Conference in Sacramento where Dutton and Wolfe (who by that time had become superstars in the Food World) presented the findings of their full study that was about to be published in the scientific journal Nature. One of them mentioned that Jasper Hill Farm had been so inspired by the information about their cheeses that came out of the study ey were now running a micro-biological lab of their own at the creamery and were extending the study even further.

And now the tape jerks to a halt in present day, in a basement meeting room in Shereton Denver where Kehler begins expaining what their lab was telling them and why they were doing it.

“There is a direct linear correlation between microbial diversity and complexity of flavor…if you don’t have enough enzymes in your cheese you can’t develop complexity.” Kehler explained. “And the microbial ecology of raw milk is the sum of all the practices on a farm.” This is why he later made the remark about “farming microbes” and not cows. It’s also the reason that Kelher later said, ” if the FDA ever mandates that all milk for cheesemaking must be pasteurized then we will stop farming because it will be much more effective to simply buy milk.”

A lot of JHF’s knowledge results from a business decision they made a few years ago to buy a nearby dairy farm so that they could expand their milk supply while still producing the milk using the exact same practices they had been doing on the original farm. Most famously they switched from feeding silage to using only hay and grass for roughage, and to do that AND to guarantee their supply of high quality hay every year they built the first round bale hay drying facility in the US. But what they immediately noticed in their microbiology lab was that even though the base “components” (fat, protein, sugars, minerals) of the milk from the two herds were identical, the “relative index” of indigenous microbes in the raw milk were very different. And that difference absolutely affects the flavors of the cheese made from that milk.

Initially JHF used their lab to help weed out Gram Negative microbes from both milk supplies because they are typically involved in spoilage as well including many pathogens. As an aside Kehler shows two relative indexes of the same batch of milk — the first was from the bulk tank right after milking, and the second was from the silo after the milk had been picked up and transported by a milk truck. They might as well have been from two different herds in two differnt parts of the world they were that different. The point being that microbial communities are the total result of every step between milking and ripening in the cheese vat.

Once they had “improved” their microbial communities they have since been isolating different species that are natuurally found in their raw milk, extracting the DNA, amplifying the DNA, and then having it sequenced for identification. So, for example, they have now found three completely different strains of Geotrichium candiduim (a yeast/mold critical to the rind development of many different cheese styles) in their milk and on their cheese rinds. Kehler said this is probably normal — all dairy farms are likely to have different strains of Geo — but that each farm is likely to have different mixes of many different strains of Geo found in the world, each mix specific to each farm. Even creameries that bought commercial strains of Geo were likely to harbor a mix of wild and commercial Geo on their cheeses, or — as Dutton and Wolfe showed in their study, which has also been shown in other scientific studies of cheese cultures, most notably in French Comté production — sometimes commercial cultures are undetectable within a few days or weeks having been overwhelmed by the native micro flora.

Their lab has also isolated about 50 different strains of lactic bacteria in their hay alone. “A majority of microflora in raw milk come from the outside of the cow udder,” Kehler pointed out, and this completely consistant with another session I went to at the Madison ACS which featured a Comté dairy farmer show us the process for producing the milk for that cheese: they washed and wiped the udders of their cows if necessary with water only, not even using soap and certainly not using teat dip. This is their purposeful effort to “harvest that farm’s microbes along with the milk, which is then shipped immediately to the cheese plant where it is stored overnight at 55degF(!) so that when they begin to make cheese the next day the ripening process is already well advanced and they do not add any additional cultures to make the cheese. In fact the Comté study actually did experiments of adding commercial cultures to these raw milks before a cheese make and after the curds had been processed and pressed those commercial cultures could not be detected.

At this point someone asked Kehler, basically “what about phage?” And the answer is as easy as pointing out that there is no commercial “rotation strain” for Flor Danica. There are 118 different strains of lactic bacteria identified in FD, and its that diversity that protects the overall culture from being affected by phage. Perhaps there are always phage present for a few of the lactic bacteria in FD (and again — Taste of Place — probably a different set of persistant phages at different creameries!) but not for every single strain. The same would be the case for the natural mix of microbes found in well treated raw milk — 50 alone in the hay…

I believe that Kehler said that right now JHF has banked over 500 different microbes from their raw milk, and that they no longer use commercial cultures, depending on their own raw milk for their aged cheeses, and then pulling from that library to culture their younger cheeses. “But you have to be aware that we’re isolating microbes and looking at them individually, but in reality they don’t exist in isolation but in communities.” That’s why starting with raw milk whenever possible is still really important to them.

In a somewhat unrelated, but visually stunning and possibly related area, JHF is finding that the strains they are isolating are already showing an ability to mutate. So once isolated strains, when re-cultured, can possibly show variant types. This opens the possibility for JHF to not only have a “library” of local strains but at any time in the future that library may expand with desirable mutant strains that sponaneously develop! During the question and answer period someone asked, “if the relative index of indigenous microbes can change so much depending on how you handle the milk, and if strains seem to spontaneously mutate, how can their be such a thing as a ‘traditional cheese?'” Kehler and Dixon agreed that it’s more probabable that the heritage European cheese we make today that are made “the same way” as they were 100 or more years ago probably taste very different than they used to. Microbial communities are not only specific to a place and its farming methods, but they are more than likely temporal as well…

PETER DIXON, on the other hand doesn’t have a microbiology lab in his creamery — Parrish Hill — so he has not been amplifying and identifying DNA sequences, but he is also working on the ngs as JHF. Instead he has looked back to the traditional methods, developed in some cases for thousands of years, and then he has synthesized those methods into one that allows him to make all of his cheese from his own starters. The techniques that he researched are:

- Pre-ripening — the natural souring action of holding your cheese milk overnight of long enough for the indigenous lactic bacteria to multiply and begin to drop the pH

- Pied de Cuveé — also known as “backslopping” which takes the whey from the previous day’s make and adds that to today’s molk to begin the ripening.

- Clabber— which has you propogate one specific culture starting with a spoonful of the mother culture into sterile milk to make a starter for the next batch of cheese.

- Cooked Curd Whey— similar to backslopping except the whey is heated to around 135degF before it’s added to the next make.

- Caillette— this is when de-albuminized whey (after making ricotta) is added to a rennet vel for soaking, which adds cultures and rennet to the next batch.

and today he uses a combination of the Clabber and the Caillette techniques, depending on the type of cheese he is making. He started them all with fresh raw milk from what he calls his Four Grandmother cows: Abagail, Sonia, Helga, and Clothetilde. And even though they are each slightly different cultures he does rotate between them just in case.

At this point Dixon handed the mike over to his Parrish Hill partner Rachel Fritz-Schall who told the story of how The Cornerstone Project began as an extension of the work Peter had been doing since 2001 and were now focused on completely at Parrish Hill. The idea was for sympathetic cheese makers everywhere to create cheeses of a similar type using their own cultures in such a way that they could all be co-markets under the umbrella of the Project and they would serve as a way to spread the word about this idea to other cheesemakers as well as consumers.

She called the basic elements of the Project: Rachel’s Rules

- all the milk must come from one herd

- it will be made with raw milk

- everyone will use the same forms and make a similar weight form

- it will have a natural rind — no washing or adding of ripening molds

- the culture and rennet will be propogated using the Caillette method

- total annual production will be < 5000 pounds

2017 will be the the first year of the Project with four different participating cheesemakers, but after they gain the experience from this first year they hope to enlist more cheese makers each following year.

THE CASE FOR HERITAGE BREEDS IN COMMERCIAL ARTISAN CHEESE PRODUCTION

This was the Dapne Zephos Teaching Award presentation by the cheesemaker — Sam Frank — who won the DZTA scholarship in 2016. Frank chose to use the scholarship money to travel in the US, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Ireland, and Scotland researching the state of cheese making that depends on rare dairy breeds. What he found was many inspiring stories and amazing cheeses made from the milk of dairy breeds that are perfectly suited to their native environment, but overall a steady decline in the use of rare breeds for milk and cheese in all of these areas.

Before he began to talk about what he found in his research he wanted us to keep in mind the following figures:

- modern Holstein cows average 11,500 liters of milk per lactation

- modern Jersey cows average 8,200 liters/lactation

Frank started is in the Noth America with the American Milking Devon at the Flack Family Farm in Enosburg Falls, VT. According to Flack the AMD is critically endangered with only about 500 animals left. It’s history in the US goes back to colonial time (thought to have been brought on the Mayflower as well as subsequent ships), though the British arm of the breed is now extinct. The Breed Association website does not list their milk production statistics, only to say that cows have “adequate milk production to raise a calf and for use on the small farm.” Flack claims that cheese yield for Devons is 20% which be twice as much as most cows milk.

Next he visited some Randall Cattle at Winter Hill Farm in Freeport, ME (shut out to Sarah and Steve!) which originally came from a closed herd in Sunderland, VT owned by the Randall family that was dispersed in 1985. It’s thought to be a unique mixture of what used to be called the “native cattle” of New England from before the time when specific breeds took over American dairy farms.

After a brief interruption* to his talk Frank brought up the Cannadienne breed which derives from cattle in Normandy and Brittany but are now “standardized” in North America. Interestingly the breed can be quite an efficient dairy animal, producing 7000 liters of milk per lactation with excellent components for cheese. According to the Livestock Conservancy the Canadienne is Critically endangered.

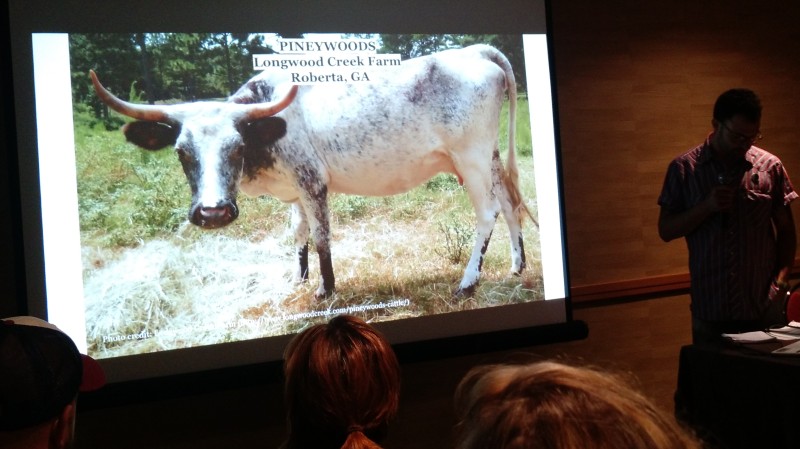

The last Noth American breed Frank researched was the Pineywood, a southern heat-tolerant US breed that has links to the original Spanish cattle that came over with the early explorers. However it has not been not selected for dairy and is normally raised for beef.

Off to Euope now, first to Spain where Frank found the few remaining flocks of Guadarama goats that are so “wild” they cannot survive confinement. The ewes will produce around 3 liters of milk a day, which is pretty good, and right now the largest extant herd contributes its milk to a single cheese maker in the Madrid region to make Quesos La Cabezuela that is sold locally. However there are currently only 8000 individuals of thsi breed left.

The numbers are much better for the Basque flagship Latxas Rubias sheep that are necessary to make Idiazabal cheese according to its PDO. And because this is a very popular cheese it supports about 750,000 of these animals across northern Spain. In addition the Basque region supports efforts to maintain and improve this breed offering many services like AI for little or no money.

Keeping with sheep Frank then traveled to Sicily to check out the Val Del Belice sheep, which are primarily used to make a two week old pasta filata cheese that is local to the region. Also in Sicily Frank found the Modicana cow, which is a very old breed of unknown origin. It’s bred to be molked seasonally, from September through May, which is the “green season” when the animals can survive on pasture alone. They also have a fairly good efficiency producing 5-7000 liters per lactation, and much of this goes into making Ragusano cheese an interesting, rectangular, “only in Italy” aged cheese.

Next Frank visited Emilia-Romagna to find the Vacche Rosse, the traditional cow for making Parmagiano Reggiano cheese, and legendarily brought to Italy by the Barbarian hoards in 600AD. The sad thing about this breed is that as recently as 1980 there were 180,000 members of this cattle breed happily making milk for cheese, but then modernization struck hard and by 2000 there were less than one thousand animals left. Today there are still only about 2000 animals, and those who still make Parm with this milk have banded together in a cooperative that are able to label their cheeses as such.

Further north, into the Alps, Frank checks in on the Simmental cow, also popular up until recently in Switzerland. But as the traditional practice of transhumance (moving cows up into the mountains in the summer) is practiced less and less, high volume breeds like Holstein become more cost effective for dairy farmers and the Simmentals are being left behind. Today there are about 25,000 of them left in Switzerland, which is a small percentage of all the cows in Switzerland. Additionally they are being crossed with Red Holsteins to produce a hybrid breed called “Fleckvieh” that produces more milk than a pure Simmental, but with higher solids for better cheese making than a Holstein. One advantage of the Simmental is that high quality of and high demand for their meat. Frank reported that a Simmental dairy farmer he spoke to had just slaughtered a 15 year old cow and had received over 4000 Euros for her carcass. This is not the case with the crosses or the Holsteins, so there are more reasons for farmers to hang onto this breed than tradition only.

Due to language issues Frank was unable to spend much time in France, let alone arrange for farm visits, so the next area he focused on was Ireland where he learned about the Kerry breed of cow, which has been documented in literature going back to 2000 BC. The Kerry is called “the first dairy breed” and has been shown to be the very best producer of milk pound for pound of any breed. The problem is they are small by modern breed standards, and a good yielding Kerry will produce only 5000 liters per lactation.

Rarer still than the Kerry’s in Ireland are the Droimeann (he pronounced it “dremmen”). Although they are very good on marginal forage typical in Ireland and are capable of producing 7000 liters per lactation, they are not widely used in dairy operations. Nor are the Irish Moiled cown, which is the only known surviving cow from Northern Ireland. One single cheese maker in County Rosscommon has a tiny herd from which he makes a fresh lactic cheese called Cloonconra that is sold only locally.

Across the Irish Sea, Scotland is famous for the Ayrshire breed of cattle that, though not critically endangered like many of the breeds listed above, they’re still on a downward track as Holsteins and Jerseys continue to gain in local dairies. In Scotland there is only one PDO cheese, Dunlop, which is required to be made with the milk of Ayrshires. Frank also learned that the components of Ayrshire milk are not only perfect for making cheese, but they’re also perfect for creating the ideal long-lasting foam on a latté, and there is one farm that Frank learned about that is selling all of its milk now directly to specialty coffee makers in Scotland and England for exactly that purpose.

South of Hadrian’s Wall in England Frank learned about the Old Gloucester breed of cow, which seems to have many of the same features of the aurochs, the very distant progenitor of modern cattle, the last known of which was seen in Poland the 1600s. Its milk is used in the production of Single and Double Goucester cheese.

Closer to Scotland, in Northern Yorkshire, a newish farm (Low Riggs Farm) is attempting to bring back the Northern Dairy Shorthorn cattle. This breed is really the only breed suited to the extreme conditions of the Yorkshire hills and dales, and its milk is the missing ingredient in making true Wenslydale cheeses. The trick will be making a good enough product that will be able to fetch a high enough price to justify the incredibly low yield of these cows in this environment — 1800 liters per lactation. They are still in the product development stage, so it is not a sure bet. But, having met the farmers — Andrew and Sally Hatten — at the Science of Artisan Cheesemaking conference last summer, I can tell you that if anyone can make it work it is them.

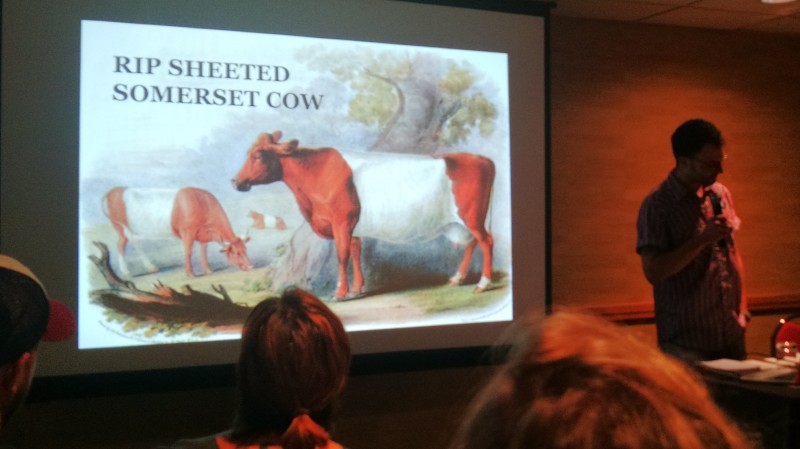

Alas, Frank’s research did not always turn up working herds of the breeds he was seeking, however small. In some cases they resulted in obituaries for breeds such as the Fribourg cattle of Switzerland last known in th 1970s, and the Somerset cow (the original Cheddar cattle!).

One interesting breed he ran into recently, just playing a hunch and searching on the Interwebs, was finding that the goat breed that made Loire cheve famous — the Massif Central Goat — still existed, just in very small numbers (which he wasn’t able to verify on the ground at the time of this presentation). As with many of these breeds there is still hope…it just doesn’t look good at the moment.

*ask me!

FESTIVAL OF CHEESE

As is always the case, the ACS Conference concludes with a massive blowout cheese party, this year made all the more massive by a record 2000+ competition entries.

Recently they’ve been serving all the soft and liquid cheeses early on the third day as the “Brunch of Champions” where I was able to do a little product research among the different cottage cheese entries (not impressed!) and I caught Rachel Bell hanging around the Kefir table…

Brunch of Champions

This year the Sheraton host hotel must not have been able to provide the logistics for the event because it was held DEEP in the halls of the MASSIVE Colorado Convention Center located about five blocks away from the Sheraton. However, once you entered the Center it seemed like you had to walk another five blocks before you got to the enormous hall that held this year’s cheese blow-out. As they’ve done for the past five years or so they let in only the media members (local and national) to see/taste the entire display “unaltered” an hour before allowing the Members only in for an hour with the display. After that they sell tickets to the public to experience this (for most people) a once in a lifetime opportunity to cheese out. As always they handed us a wine glass and a strangely effective plastic tray for holding lots of cheese and other food samples and then let us loose. I did a quick turn around the outside edge to see what non-cheese offerings there were, stocked up on a few, and then dove in.

This year the Sheraton host hotel must not have been able to provide the logistics for the event because it was held DEEP in the halls of the MASSIVE Colorado Convention Center located about five blocks away from the Sheraton. However, once you entered the Center it seemed like you had to walk another five blocks before you got to the enormous hall that held this year’s cheese blow-out. As they’ve done for the past five years or so they let in only the media members (local and national) to see/taste the entire display “unaltered” an hour before allowing the Members only in for an hour with the display. After that they sell tickets to the public to experience this (for most people) a once in a lifetime opportunity to cheese out. As always they handed us a wine glass and a strangely effective plastic tray for holding lots of cheese and other food samples and then let us loose. I did a quick turn around the outside edge to see what non-cheese offerings there were, stocked up on a few, and then dove in.

My strategy this year was to immediately scope out the non-cheese offerings which are on the perimeter around the table groupings by different cheese type. Another reason for this is that I had met a Colorado hard apple cider maker at the opening receptions on Thursday night where he was serving only one of his ciders on tap, and he told me that he would also be at The Festival with a bunch more of his ciders in bottles. I told him that I was a cider “enthusiast” and that I made my own cider from my own apple trees, some of which I had planted myself. Therefore he really wanted me to taste their first bottled cider from a group of 11 heirloom cider apple trees he planted in 2013. Appropriately enough it was called “First Block” and it was super duper good. (I was also not a surprise that he knew several of the serious New England cider folks, including John Bunker at Fedco Trees!)

My strategy this year was to immediately scope out the non-cheese offerings which are on the perimeter around the table groupings by different cheese type. Another reason for this is that I had met a Colorado hard apple cider maker at the opening receptions on Thursday night where he was serving only one of his ciders on tap, and he told me that he would also be at The Festival with a bunch more of his ciders in bottles. I told him that I was a cider “enthusiast” and that I made my own cider from my own apple trees, some of which I had planted myself. Therefore he really wanted me to taste their first bottled cider from a group of 11 heirloom cider apple trees he planted in 2013. Appropriately enough it was called “First Block” and it was super duper good. (I was also not a surprise that he knew several of the serious New England cider folks, including John Bunker at Fedco Trees!)

CONGRATULATIONS to Fuzzy Udder for the Win with Windswept!

Must. Pace. Myself…

A BETTER way to approach things…more balanced.

…and my winner IS — Ghost Pepper Jack. EXTREMELY hot, but a full and balanced cheese flavor that perfectly complimented the flavor of the peppers. Ghost Peppers are like little Napalm Nuggets and I’ve never tried a dish that used them that didn’t get completely overwhelmed by the heat of the pepper. So making this cheese must have been very much like being one of the characters in The Hurt Locker. Kudos.

And, then, ooofffff…time to go home.